Thomas

Healy Remembers

“In every breath

we speak what we know,

Being what we are.

I am a man of good intention.

...

I have not hurried a difficult

Day by praying for night.

I extinguished

no candle before its hour.

I have not tested the limits imposed by gods

Nor tried to turn back the stampede of events

That brought me to my knees

and destiny.”

From

“Confession,” in Awakening Osiris: The Egyptian Book of the Dead, by

Normandi Ellis (Phanes Press, 1988)

~~~~

The

Legacy of Lono

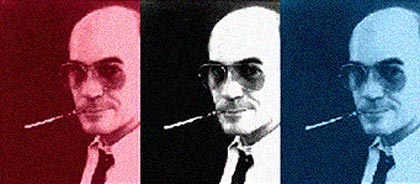

by Thomas

P. Healy

At the conclusion

of The Curse of Lono, author Hunter S. Thompson’s scathing report on the

“body Nazis” who participate in the Honolulu Marathon, he makes a claim

that he is Lono, the ancient Hawaiian god of agriculture and peace.

At

a public talk around the time the book came out, I took advantage of the Q&A

to ask about the ending. “At the end of The Curse of Lono, you leave the

reader thinking that you’re God — a god named Lono. My question is,

did you give up religion for the same reason as politics” — no money

in it, he’d written — “or are you, in fact, God?”

He

had a good laugh at that but quickly turned deadly serious. “No, I am Lono.”

Gonzo

journalist as shaman

“In

traditional societies shamans are often known as ‘masters of death,’”

writes Neville Drury in The Visionary Human: Mystical Consciousness & Paranormal

Perspectives. “And they have been defined by Mircea Eliade as ecstatics capable

of making a visionary journey from one plane of reality to another.”

By

his own reckoning Thompson had nearly died some 15 times. Each return from the

“journey” — whether beaten by Hell’s Angels or by Chicago

cops — he had a story to tell.

As

Drury noted, “The shaman returns to earth consciousness with … ‘spiritual

revelations’ … and in traditional shamanic societies such revelations

become part of that culture’s accumulated ‘wisdom teaching.’”

“Like

tribal shamans, the artists saw themselves, in Ezra Pound’s phrase, as ‘the

antennae of the race,’” Daniel Pinchbeck writes in his study of contemporary

shamanism, Breaking Open the Head.He suggests that both 19th-century Romantic

poets and Modernist writers emulated shamanic practices. “In a secular culture,

they were the ones who journeyed into the land of the dead, who crafted images

of an elusive sublime, who went into ecstatic states of inspiration.”

Journalists

such as Thompson, John Reed, Studs Terkel, Ida Tarbell and Mollie Ivins certainly

qualify as the “antennae of the race” — reporting on the view from

“the other side.” Unlike these more conventional journalists, Thompson’s

methods can be seen in a shamanic light. In virtually every article, he is in

search of “the nut” of his story and generally it involved journeying

in some “non-ordinary reality” that could be brought on by the systematic

derangement of the senses via chemical means, by sleep deprivation and unbridled

paranoia during a deadline frenzy or by raw amazement at the listless stupidity

of “normal” life.

When

he “returned” from his wanderings into the “savage heart of the

American Dream” in Las Vegas or survived a campaign in the “vicious

business” of presidential politics, he crafted tales of “fear and loathing”

that illuminated, informed and inspired his tribe and entered into the cultural

lexicon.

Thompson’s

obscenity-laced texts led some readers to question his skill with language. In

his reply to one appalled reader, who cancelled her subscription to Rolling Stone

in a letter that said “profanity is a crutch for conversational cripples,”

HST said, “[W]ords are just tools, for a writer, and when I write about Richard

Nixon I’ll use all the tools I can get my hands on, to make people like you

think about why Richard Nixon was elected by a landslide in 1972. My primary idea,

whenever I sit down to write, is to get the attention of people like you and make

youthink.”

Having

referred to Richard M. Nixon in the past as a “cheap, thieving little bastard,”

and a “criminal geek,” in recent years Thompson actually grew a bit

wistful about his arch nemesis. In his last piece for Rolling Stone he wrote,

“Nixon was a professional politician and I despised everything he stood for

— but if he were running for president against the evil Bush-Cheney gang,

I would happily vote for him.”

He

went on to predict a Kerry win, and called George W. Bush “a treacherous

little freak” and “a natural-born loser with a filthy-rich daddy who

pimped his son out to rich oil-mongers.”

No

other journalist in the world would have the guts to say such a thing out loud,

much less publish it in a mass-circulation periodical. But Hunter was like no

other journalist in the world.

Gonzo

journalist as outlaw

“To

live outside the law, you must be honest,” sang Bob Dylan, one of HST’s

favorite musicians. “I always figured I would live on the margins of society,

part of a very small Outlaw segment,” Thompson wrote in his 2003 book, Kingdom

of Fear. “I have never been approved by any majority. Most people assume

it’s difficult to live this way, and they are right — they’re still

trying to lock me up all the time. I’ve been very careful about urging people

who cannot live outside the law to throw off the traces and run amok. Some are

not made for the Outlaw life.”

His

novel approach to writing, dubbed “outlaw journalism,” “new journalism”

or his own preferred “Gonzo journalism,” was an instinctual response

to what he saw as the need to get inside a story and tell it from the perspective

of radical subjectivity.

He

knew from the time he was 16 he wanted to write. “That was all that really

interested me,” he told writer P.J. O’Rourke in an interview for Rolling

Stone magazine’s 20th anniversary issue in 1987. “Actually, learning

interested me. Learning still does. That’s the main thing about journalism:

it allows you to keep learning and get paid for it.”

It

was a long, strange trip from his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, to his “fortified

compound near Aspen, Colorado,” fueled by almost any and every legal and

illegal substance a boy or man could put his hands on.

An

act of belligerence on his part got him into the Armed Forces: when given the

choice after a series of youthful indiscretions, he opted for military service

rather than jail. He later refused to accept a security clearance from the Air

Force on the grounds that he didn’t consider himself a good security risk

“because I disagreed strongly with the slogan, ‘My Country, Right or

Wrong.’” His punishment? “I was passed over for promotion and placed

in a job as sports editor of a base newspaper on the Gulf Coast of Florida.”

There

was no turning back. In that most precarious of careers, freelance writing, Thompson

spent the next 40-plus years sharing his careening life up close and personal

during a time of unprecedented transformation in the country’s political

landscape: through post-JFK-assassination America into the rice paddies of Vietnam

and Cambodia; the “police riot” at the ’68 Chicago Democratic Convention;

the “dark and venal” Nixon years and his subsequent humiliating departure

from the White House; the hopeful Carter years when the country came close to

decriminalizing personal recreational drugs; the fascist (using Mussolini’s

definition of fascism as “corporatism”) onslaught of the Reagan years,

further developed during the first Bush presidency; the Clinton/Lewinsky detour;

and on up to the “president-select” in 2000 and now the “re-elected”

fortunate son, George W. Bush, whom HST described in Kingdom of Fear as “a

bogus rich kid in charge of the White House.”

In

the editor’s note for Fear and Loathing in America: The Gonzo Letters, Volume

II — Thompson’s correspondence from 1968-1976 — historian Douglas

Brinkley writes, “As a pure literary art form, Gonzo requires virtually no

rewriting: the reporter and his quest for information are central to the story,

told via a fusion of bedrock reality and stark fantasy in a way that is meant

to amuse both the author and the reader. Stream-of-consciousness, article excerpts,

transcribed interviews, telephone conversations — these are the elements

of a piece of aggressively subjective Gonzo journalism. ‘It is a style of

reporting based on William Faulkner’s idea that the best fiction is far more

true than any kind of journalism,’ Thompson has noted.”

“I

just usually go with my own taste,” HST said in a Paris Review interview

in 2000. “I wasn’t trying to be an outlaw writer. I never heard of that

term; somebody else made it up.”

While

an outlaw journalist might take a dim view of deadlines, paltry word counts and

expense account limits, he is not a criminal, say, in the way a journalist is

who “outs” a covert CIA operative. That’s a felony, by the way,

if anyone bothers to prosecute. An outlaw journalist isn’t a stenographer

to the powerful and would never run verbatim transcripts of White House press

briefings with the excuse, “If I am communicating to my readers exactly what

the White House believes on any certain issue, that’s reporting to them an

unvarnished, unfiltered version of what they believe.”

But

it’s a postmodern world where a poseur like Guckert/Gannon can get day passes

as a White House correspondent so he can transcribe Scott McClellan’s remarks

but Maureen Dowd at the New York Times, who might ask a tough question or two,

is denied access.

When

Hunter had a press pass to the White House while covering Nixon’s departure,

he used the access to file uncompromising stories for Rolling Stonethat are unthinkable

in today’s self-preservation-oriented journalism herd-mentality.

“[T]he

climate of those years was so grim that half the Washington press corps spent

more time worrying about having their telephones tapped than they did about risking

the wrath of … a Mafia-style administration that began cannibalizing the

whole government; they swaggered into Washington like a conquering army, and the

climate of fear then engendered apparently neutralized the New York Times along

with all the other pockets of potential resistance,” he wrote.

His

comments about the neutralized “Gray Lady” during the Nixon administration

could just as easily serve as a contemporary coda to Howard Friel and Richard

Falk’s convincing brief against the “paper of record” in The Record

of the Paper, which outlines the Times’ inability and/or unwillingness to

consider numerous violations of international law in its coverage of U.S. foreign

policy.

As a maniacal

freelancer, HST wrote for the Times Magazine, as well as Time-Life publications

and a score of notable and forgettable periodicals. He wasn’t interested

in the life of a time-clock puncher.

He told Peter Whitmer, “Journalism

has always seemed a good way to get someone else to pay to get me where the action

really is.”

Like the

old-school journalists who called in 50-paragraph stories to the office, Thompson

usually composed on-the-spot narratives from his notes, a reporting skill that

takes tremendous focus, dedication and a firm grasp of the subject matter.

Thompson’s

style was a direct descendent of the traditional method, but instead of 50 paragraphs,

he’d submit 15,000-word screeds using a primordial fax machine, the technology

of the fabled “mojo wire” — a low-resolution and low-reliability

machine for transmitting text in pre-PC days — that has since been overtaken

by wireless computer networks, cell phones and e-mail. In this technological milieu,

HST’s most natural offspring are the bloggers.

Highly

personal, unfettered by so-called journalistic objectivity and deadline constraints,

blogs are a vestige of Gonzo journalism that deserve recognition as part of Thompson’s

legacy.

Gonzo Journalist

as Warrior

Author Barry

Miles, whose most recent biography of Frank Zappa follows other life stories of

counterculture heroes such as Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac

and Paul McCartney, writes, “Zappa is an iconoclast in the male American

tradition of Neal Cassady, Hunter S. Thompson, William S. Burroughs, Ken Kesey,

Allen Ginsberg, Lenny Bruce and the early Norman Mailer.”

The

Heartland iconoclast was not just a psychedelic hillbilly drunkard but also a

keen intellectual, a brilliant political analyst and a gifted, determined craftsman

who persevered against tremendous odds to tell his readers that there are options

for resistance, that we can send a message to the fixers and greedheads to say

that while they will always be among us, we are not afraid to meet them head on,

to speak our truths and to stand our ground to the bitter end.

“He

was an old, sick, and very troubled man, and the illusion of peace and contentment

was not enough for him. ... So finally, and for what he must have thought the

best of reasons, he ended it with a shotgun.”

— Hunter S. Thompson

These

closing words from a 1964 National Observer piece about a pilgrimage to Hemingway’s

Ketchum, Idaho, seem remarkably prescient. The man who wrote them would, like

his hero, take his own life, in a different mountainside town, a few hundred miles

to the south, some four decades later.

But

his fans need not grieve over his final defiant act. Read long-time collaborator

Ralph Steadman’s tribute in the Guardian. “It wasn’t a question

of if, but when,” Steadman wrote in his moving essay.

We

don’t have to wonder what Thompson’s last thoughts were. His suicide

was a deliberate act — a calculated move by a man driven, as he often claimed,

to “control his environment” as an ultimate assertion of individuality.

In their public statement his family called him a warrior because his parting

shot was a courageous act. In fact, it was heroic — like a samurai warrior

who committed ritual suicide as an act of courage and honor.

Thompson

leaves behind a remarkable journalistic legacy, unrivaled in the modern era, that

chronicles the closing decades of the 20th century as well as the dawn of the

new century in a raw, savage style that manages to wring out truth in brutal honesty

without a trace of nostalgia or romanticism.

“The

rebellion of the 1960s carried with it a kind of naive sense that since we were

right, then ‘right’ would prevail and we would stop the war and find

better ways to live,” he told Peter Whitmer. But he knew better and that’s

why he interjected the word “naive.”

He

called on the power of the “people’s history” of the recent past

to remind us there were precedents to show that we could stand up to tyranny.

“We were angry and righteous in those days and there were millions of us,”

he wrote in his final Rolling Stone piece. “We kicked two chief executives

out of the White House because they were stupid warmongers. We conquered Lyndon

Johnson and we stomped on Richard Nixon — which wise people said was impossible,

but so what? It was fun. We were warriors then, and our tribe was strong like

a river.”

Yes, but

the river was dammed by the neocons and drained by the fearmongers and greedheads

whose idea of morality is gutting the Bill of Rights. I can imagine that after

four decades of chronicling the “death of the American Dream” and seeing

things go from bad to worse, Thompson was bushed.

Given

a man whose lifetime fascination with intoxication was an integral part of his

work, it’s almost ironic that the best word I can use to describe my response

to his passing is “sobering.” With all of the stories that need to be

told, all the chits that need to be called in, all the aggressive Calvinists seeking

to supplant science with superstition, sacrifice human rights for property rights

and convert the land of the free into the home of the brainwashed, Thompson’s

final gesture should not — cannot — be ignored.

Thompson

issued a wakeup call, warning of the cultural/political shitstorm that threatens

our beleaguered nation and challenging us to awaken from the nightmare of history

that has given the world George W. Bush and his cruel henchmen.

I

hope we have the courage to answer it.

©2005

Thomas P. Healy

Healy is

a journalist in Indianapolis and can be reached at apple@branches.com .